INDIGENOUS FOREST DWELLERS OF SRI Lanka: Are they on the verge of cultural extinction?

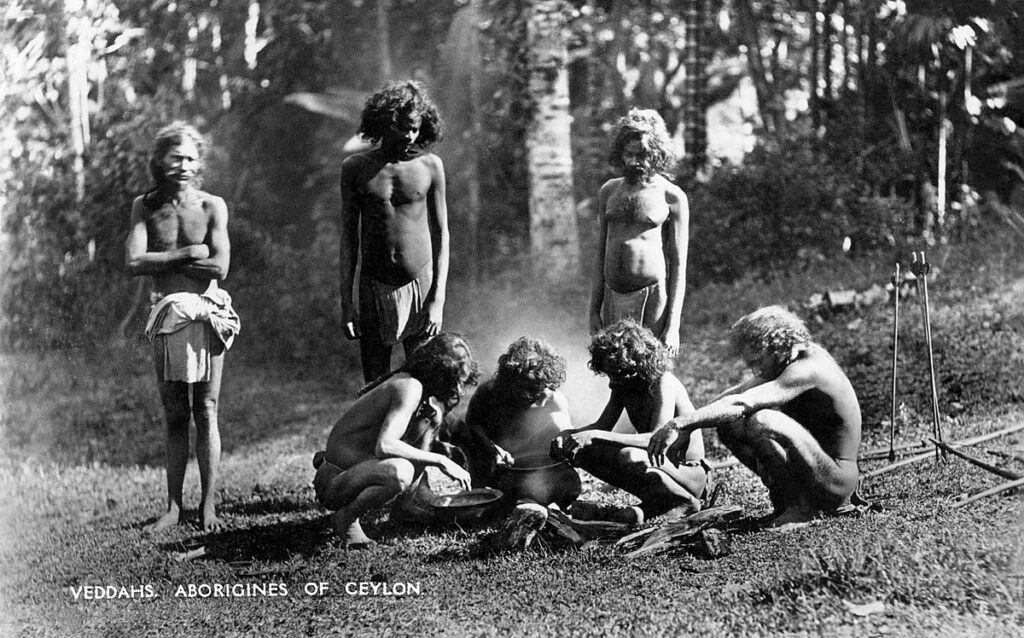

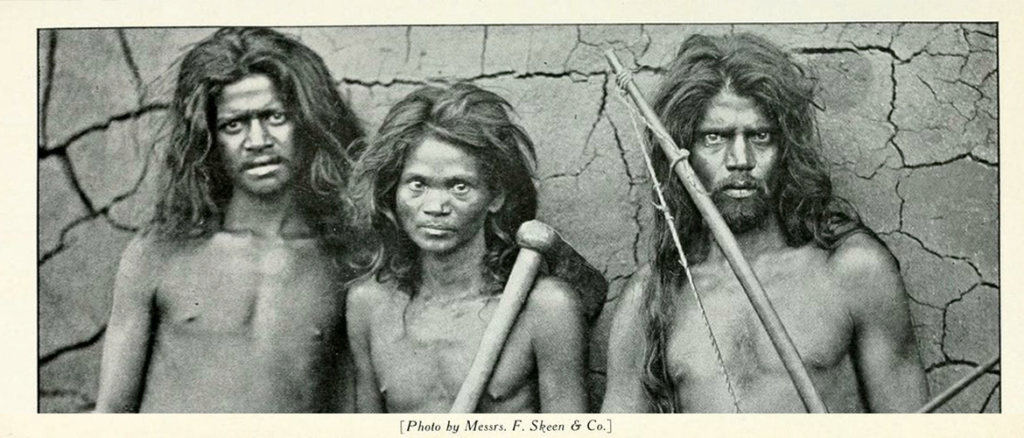

To some colonials in the 19th century these people appeared to be primitive hunter-gatherers who had a dishevelled look, spoke an uncouth language and lived in caves or roamed in the forest in search of game, using their bow and arrows. Yet, no one seemed to understand that the present so-called modernised society has much to learn from them: they remain gentle and patient towards others and despite being skilled hunters, rarely do they wield a weapon in anger. They never commit theft or fraud out of greed or raise their voice towards outsiders or quarrel. Though they may speak a little, they never tell lies. Finally, their sense of faithfulness in love which today’s society lacks, is laudable: their marriages last a life time and in their tightly-knit families the divorce is something rare.

They are the indigenous people of Sri Lanka, called “Veddas” although they call themselves “Wanniya-laetto” (forest dwellers). Some say that the word “Vedda” originates from the Pali word for “bowman”. “Vadi” in ancient Sinhalese also means “one who roams the forest”. But others say that it comes from the Tamil word “Vedan” meaning hunter. Another name given to this primitive community is “Sabara”. It is possible that the province of Sabaragamuwa (or village of the Sabara) owes its name to their presence in this region in earlier times.

It is said that the Veddas have a racial affinity to the Kadar and Chenchu people of South Asia, to the Andaman islanders and to the Semang of the Malaysian peninsula. Anthropologists have also traced their origin back to the aborigines of Australia. The Veddas are a timid racial stock of short stature. According to Mahavamsa, Pali chronicle on the history of Sri Lanka, the Veddas are the descendants of Disala and Jeevahaththa, respectively the daughter and son of the Aryan Prince Vijaya (543-505 BC), the founder of the Sinhalese race, who was exiled from his father’s kingdom in North India due to his mutinous behaviour and landed in Sri Lanka with 700 followers. On landing at a place named Thammenna in northwestern Sri Lanka, he fell in love with a beautiful princess named Kuveni from the “Yakka” (demon) tribe. Vijaya was enthroned as the first recorded Sinhalese king of Sri Lanka although he later banished his wife from the kingdom and married the daughter of an Indian king. When Kuveni went to her relatives for help, they killed her for betrayal and the two children escaped to Sabaragamuwa. Xuanzang, the 7th century Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar and pilgrim, said that the forest dwellers were referred to as “Yakkas”. Yet, anthropologists claim that the origin of the Veddas dates as far back as the Stone Age of the country. According to Prof. S. U. Deraniyagala, Sri Lanka’s former Director-General of Archaeology, the Veddas settled in every nook and cranny, ranging from the cold and misty Horton Plains in Central Sri Lanka to the arid lowlands of Mannar and Wilpattu, to the equatorial rainforests of Sabaragamuwa. Successive arrivals of Aryan and non-Aryan Dravidian immigrants and colonisers from the Indian sub-continent had an adverse effect on the insular home, occupied for uncounted millennia by the Veddas, who were compelled to leave for the arid forest plains of Uva province in eastern Sri Lanka where they struggled to preserve their age-old traditions, worldview and lifestyle. Their prehistoric cultural memory and sound knowledge of the forest helped them meet the challenges to their survival amidst outside pressure from the new communities.

Today a majority of Wanniya-laetto has taken Sinhalese or Tamil names, adopted Sinhalese or Tamil as their language, Buddhism or Hinduism mixed with their animistic beliefs as their religion, depending on where they live, as a strategy to avert extinction. They have equally adopted the diet and attire of these communities. The Veddas in the north central Anuradhapura and eastern Bintenna regions speak

Sinhalese, an Indo-European language and have taken up cultivation of rice whereas the Veddas in the predominantly Tamil east coast speak Tamil, a Dravidian language and are engaged in fishing. Nevertheless, what they speak is a creole, mixed with Sinhalese words, although linguists have noted words of unique origin in the Vedda language and a language they spoke among themselves only understood by them.

A 1978 survey had identified 6,000 Veddas in the Anuradhapura district alone. Uruwarige Vanniya, the current chieftain of the Dambana tribe and son of the respected Vedda leader Tissahamy who died in 1999 at the age of 96, said that in 2008 there were more than 1,500 families in the whole island with a majority living in Dambana and Pollebedda villages in the Uva province. Eastern Veddas live in Vakarai in Batticaloa district, numbering around 100 families.

In the distant past the Veddas dwelled in caves, several families in one cave. They hunted wild animals and gathered honey from hives, using smoke from burned dried leaves to chase the bees away. The game and food were not kept to oneself and shared among the family members and friends no matter how meagre the game was. Although men and women were treated as equals, the men had to go for hunting and gathering honey while the women had to collect vegetable roots. They practised monogamy and there was no caste system. Meats were dried or smoked, at times stuffed in the hollow of a tree, filling it with honey and then sealing it. If a person died of an illness, the Veddas would leave him in the cave and shift to another cave, covering the body of the deceased with dried leaves, only to return there after many years. They believed in the transmigration of souls and “demon relatives” or “Nae Yakku”. To avert diseases and misfortune that these dead relatives would bring forth, the Veddas conducted rituals and dances to appease them. The Vedda children received special care. The lullabies the Vedda mothers sing are probably the oldest in the world, needing to be preserved. Sung to three varying tunes and rhythms, these cradle songs are thought to be those sung by princess Kuveni to lull her two babies to sleep.

Robert Knox, English sea captain, who was held captive by King Rajasinghe II, made the first western account on Veddas in his book published in 1681. He described them as “wild men” though there was also a “tamer sort”. Later in 1881 anthropologist Rudolph Virchow published a report on them in Germany followed by British physician and ethnologist Charles Gabriel Seligman in 1911. The Sri Lankan surgeon Dr. Richard Lionel Spittel, of Dutch origin, is undoubtedly the best authority on these indigenous people. His novels on them, also translated into Sinhalese, became best-sellers in this country. His death in 1969 shocked the Vedda community who called him “Sudu Hura”, a term of endearment meaning “white-skinned gentleman”.

In 2016 the Veddas requested the authorities to embody their rights in any new constitution: right to live in the forest, hunt animals and be engaged in agriculture in harmony with the nature, give them concession for education and employment and be recognised as a separate minority community.

For its part, the government of Sri Lanka has sought to promote literacy among this community and allow them to have access to health facilities. Today the Veddas sell honey, artefacts, etc. to visiting locals and foreigners and others do odd jobs to earn a living. In Dambana there is a Wanniya-laetto Heritage Centre.

The advent of the radio, TV, mobile phones, computers, etc. seems to have brought about changes in the thinking and lifestyle of the young Vedda generation. Today they are eager to go to cities for greener pastures, to get better educational and employment opportunities, leaving the cherished traditions and customs of their elders behind. This then raises the vital question whether a Vedda should remain a Vedda all the time. Are they not entitled to be absorbed into the social and economic mainstream of the country? They do have that right! Yet, the allurement of the so-called civilised society should not be allowed to make inroads upon their moral values and worldview. ***